Recently, while waiting for the room where we are holding our English language club meetings this year in the library Музей книги блокадного города (Museum of Books of the Besieged City—a reference to the 3-year siege of this city during WW2) to become available, a journal title caught my eye. It stood out because the title touches on an area of research I’ve been investigating and writing about for some years—as posts in other areas of this substack will indicate.

I currently hold that the discussion and investigation typically conducted in this area area is fundamentally flawed on the conceptual level, which ideas interested readers can find out about by reading some of my writings on those topics. Still, I am always interested in reviewing the ideas of others who write/speak and conduct research in this area. I’ve taken a special interest in how Russians approach the matter since, on the level of vocabulary, the Russian word наука, which is often translated into English as “science,” actually does not carry many of the same connotations as our English word science does. Basically speaking, its frame of reference is far wider than that implied by our English word science.

For example, the Russian word is used for a quite varied range of topics on the intellectual spectrum—ranging from humanities subjects to things like oceanography and from psychology to philosophy and beyond. So, to entitle a journal “Science and Religion” using the word наука will not imply, in Russia, the sorts of restrictions on subject matter that the English word “science” carries—limited as that latter term is almost exclusively to natural or “hard” science areas like physics, astronomy, biology, chemistry, and the like.

In the West there are of course journals that explore the boundaries of the respective areas of science and religion as westerners conceive these areas. The journal Zygon would be one example. But for reasons mentioned, investigating these interrelations will differ in accord with the differing lingua-conceptual landscape of the West.

In this post then, I will, in the interest of fulfilling my stated aims of better informing the western audience about the intellectual landscape that obtains here, offer a bit of an overview of this newfound (to me) journal and its history.

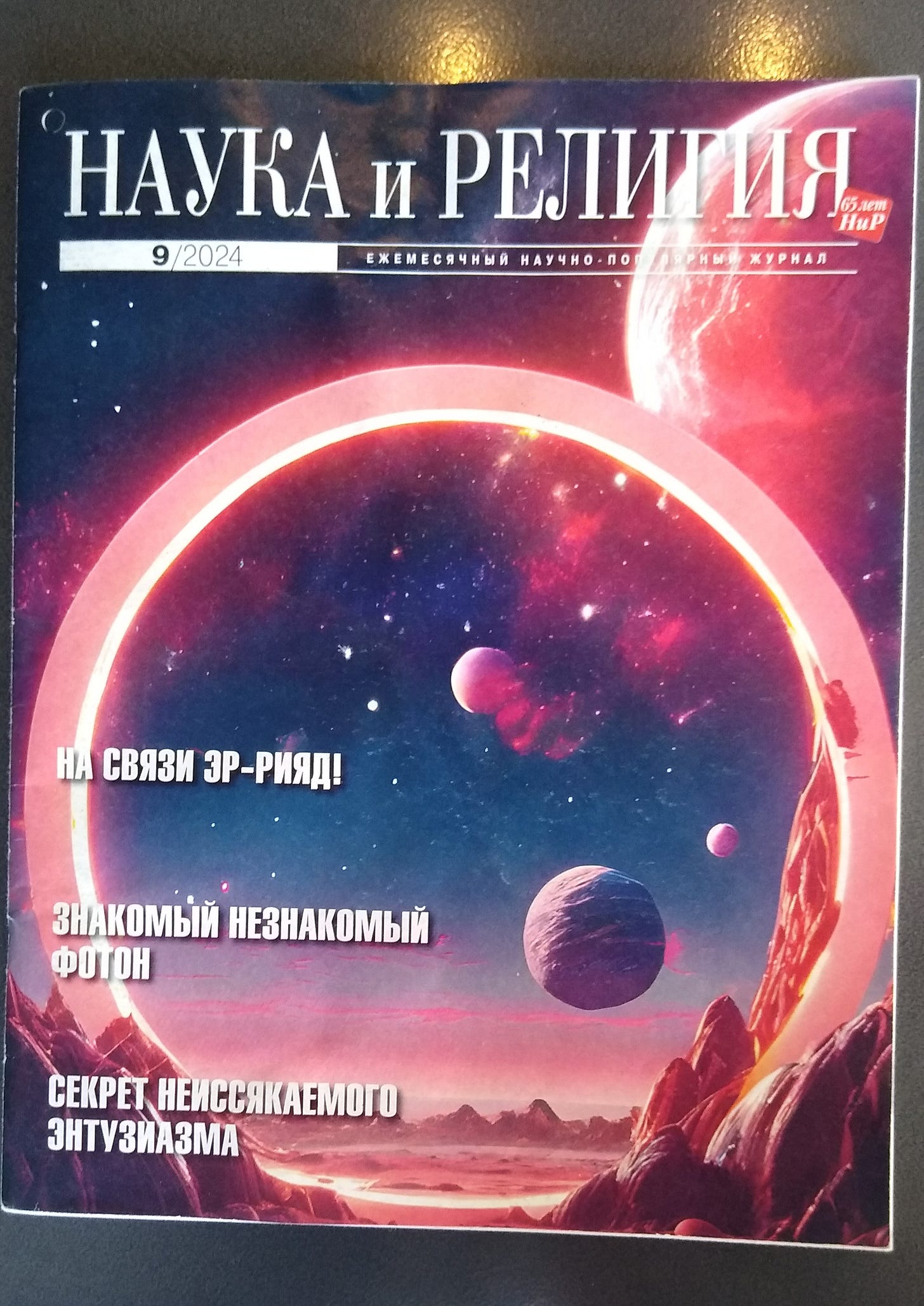

First, a bit about the title page. Especially noteworthy is the fact that, as conveyed by the small red tag to the far right of the title, the year in which this particular issue came out—namely 2024—marks the 65th year of this periodical’s publication. So this journal is interesting for the fact that it spans both the Soviet and post-Soviet eras.

Other items on the cover depicted translate into English as follows: Scientific-popular journal (just under the title); Riyadh calling; Familiar/Unfamiliar Photon; The Secret of Inexhaustible Enthusiasm.

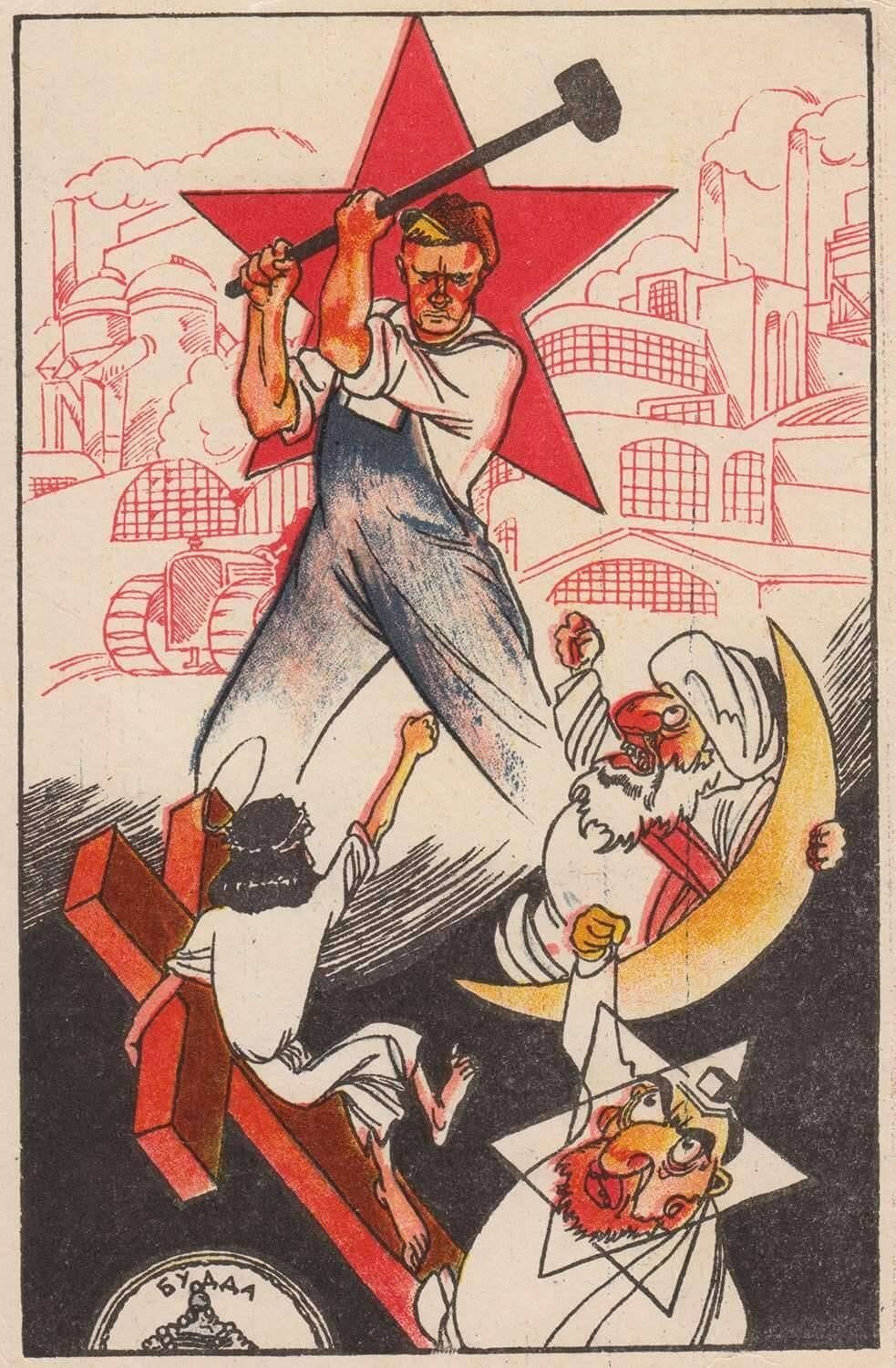

As we should all be aware, the Soviet state was officially atheist, taking as its stated aim the eradication of the phenomenon of religion. Given that reality, one would expect that, in the Soviet era, a publication going under the title “Science and Religion” might have a specific, adversarial slant with regard to these two areas. In other words, it would be expected that the pages of this journal would be filled with writings trumpeting the ways in which natural science had supplanted and superseded religion and religious thinking, along similar lines to the crude depiction in the photo of a Soviet propaganda poster below:

Though I’ve not yet managed to examine earlier editions of this journal, which dates back as far as 1959, to confirm my suspicions, that is what I would expect to find in its pages. And, in fact, in a brief article from the editor in the 2024 issue depicted above where a bit of its history is summarized, that is explicitly stated. As Sergei Klyuchnikov avers, the “journal was conceived as an instrument in the fight against religion.” (“A Word from the Editor,” p 2)

As he also notes in his comments, however, many of those actually writing for the journal conceived their task somewhat differently. They, to the contrary, saw in publishing for this journal an opportunity to expose readers living under an officially atheist regime to the variety of traditional faith systems extant in the world’s surrounding, non-atheist, polities and cultures. So, many of the contributors wound up playing a somewhat subversive role with regard to the journal’s founding mandate, according to Klyuchnikov’s brief accounting.

The shift from atheistic polemic to the journal’s current content must have been fairly sudden given the rapid collapse of the Soviet regime in the late-1980’s/early 1990’s. I very much hope to have a look through some of the issues published over the course of the journal’s history, particularly those around its inception in 1959 and others around the year 1990. The Russian National Library, located only about a mile from where I now sit, should have all those issues. Perhaps I will post here a follow-up on that.

As to the content of the journal in its current iteration, though it is somewhat ecumenical in its approach to presenting the world’s religious traditions, there seems to be a major emphasis on the Orthodox church with its traditions and culture. At the same time, there seems to be at least some of what we westerners would consider science proper, as, for example, the article about photons.

Additionally, there is at least some content that one would not expect to find in a journal going under such a title in the West: for example there is a brief section toward the end of the recent issues I’ve inspected that is more or less horoscopic or magistic, offering advice about which days of the month are to be considered more or less fortuitous in view of the phases of the moon and other astronomical observations. I’ve so far managed to examine only a few very recent copies of this journal, and they all contain this same small section at the end. I would be curious to see how far back in its publication history this segment extends.

So that is the report for now on this topic. Once I am able to make it over the the Russian National Library to consult some of the older issues I mentioned, I intend to post another article on this topic.