Hiatus from hot water and "sanitary day"

No, those two things are not necessarily connected in this post

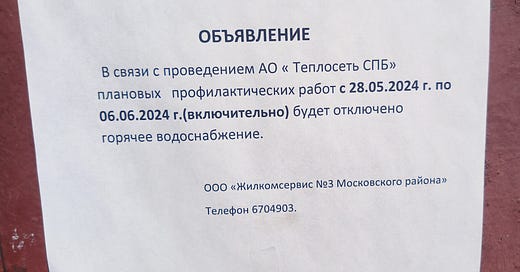

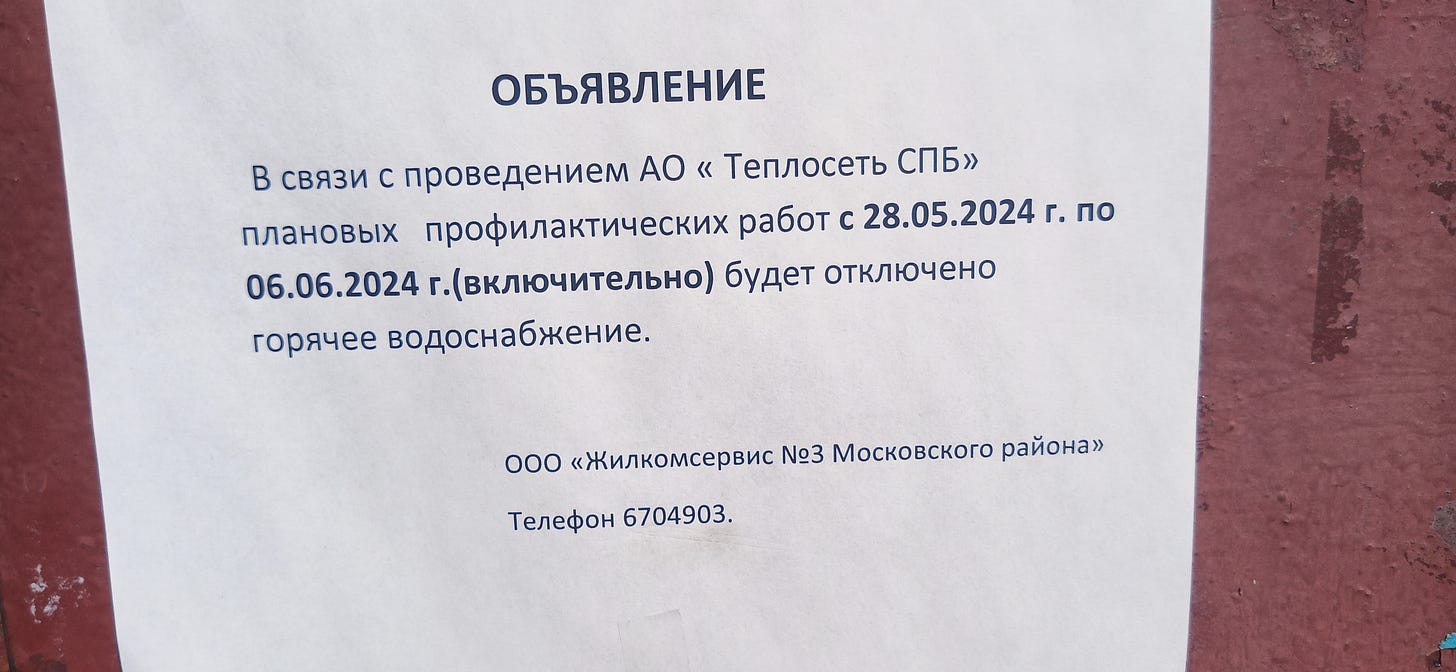

The notice we found on our apartment building’s door the other day and as seen in the photo above was not at all unexpected. As I’ve come to understand, this sort of announcement has been a standard part of Russian life for decades, and it’s something many Russians expect over the course of a summer.

A translation of the notice follows: “In connection with the execution of planned preventative maintenance by the Joint Stock Company ‘St. Petersburg heating system,’ hot water provision will be disrupted from May 28th through June 6th 2024 inclusive.” The import of this notice, as Russians will understand, is that no hot water will be available, during the dates listed, through the plumbing system in apartments located in such buildings at which these notices have been posted.

The interval during which hot water is shut off varies within Russia; it can be from anywhere up to one month to perhaps just a day or two. We were expecting the median period of about 2 weeks of hot water hiatus at the apartment where we lived last year, but it actually wound up being only one day. This year, on the other hand, it looks like the hiatus will last close to 10 days at our new apartment. So, no warm showers here, and no hot wash cycles for laundry or dishwashers, for the next several days.

This odd system—at least for Americans—is actually a relic of Russia’s socialist past. Under the Soviet system, heat and hot water, along with other utilities, were provided to most citizens by a state-owned entity. In larger cities, there would be one or more plants at which steam and hot water were produced for entire neighborhoods. Those boiler plants required maintenance at least annually, so it was standard practice to shut them down when demand was at a minimum so as to perform that maintenance. In other words, during the summer months.

Russia is still in the process of transitioning from a socialist system of governance with its accompanying infrastructure, toward a more of a free-market system such as exists in most western countries. So remnants of the old system still remain here. Provision of utilities is one such area.

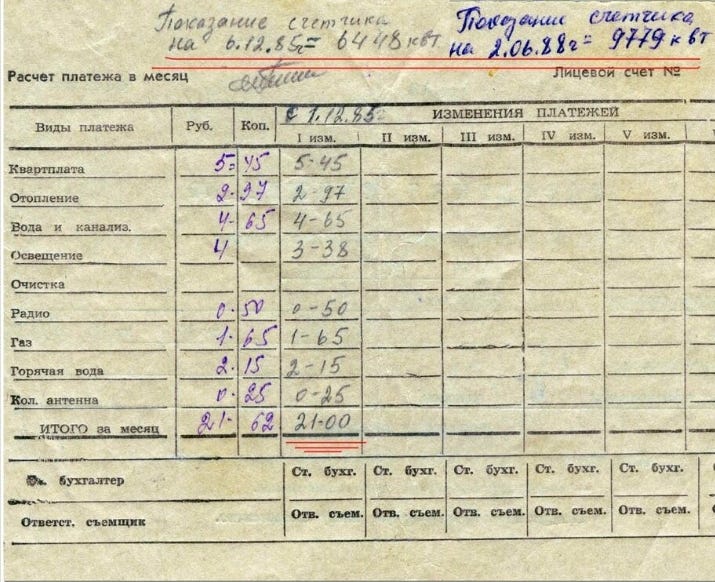

For hot water and heat, residents of most apartment complexes—meaning most residents of cities like St. Petersburg—pay a set monthly fee during heating season for the water that is heated at those central boiler plants. The average cost seems to be around 2,500 rubles per month (roughly 30 USD at current exchange rates). When heating season ends, residents pay no such fees until the next heating season starts. When heating season starts and ends is, in turn, based on average ambient outside temperature as determined by the entities that supply hot water. There is some variability in the cost to residents, with higher or lower monthly fees for those living in larger or smaller apartments—size being a matter of the cubic meters occupied by the unit in question.

Most residents of Russian apartment buildings in larger cities have excess heat during heating season. It is typical for many apartment dwellers to keep one or more windows open, even during very cold weather, to help moderate inside temperatures. Another strategy sometimes used, either in combination with window-opening or separately, is to turn off hot water flow to one or more of the radiators located in any given apartment.

That is the way things work for heat and hot water provision for a majority Russians and it is a system that has been in place for decades, stretching back even into the Soviet era. The difference between the two eras, in percentage terms, is that residents now pay, on average, about 15% of their salary for utilities (heat and hot water included), while in Soviet times they paid a little over 11% during heating season. During non-heating months that current percentage gets down closer to what it was during Soviet times.

Natural gas is another commodity that, for apartment dwellers, is paid for at a set monthly fee. The fee is, in turn, based on how many gas-consuming appliances the household has. For example an apartment that has only a gas stove will pay a lower monthly fee than one that has both a gas stove and a gas water heater (those with on-demand water heaters—the type that seem to be the norm here—are unaffected by the annual boiler shutdowns). But, as with heat and hot water, there is no metering involved; in other words, no meter tracks volume of gas used and so the charge is not based on volume, except in a very general way.

For single-occupancy homes—which tend to be located in what Americans might think of as bedroom communities—gas meters are actually employed. The total population living in such circumstances in Russia, unlike in the U.S. and likely other western countries, is far smaller in Russia than the population living in large apartment or condo complexes.

It seems electric meters have been another part of life in Russian that, apart from cost, has remained consistent since the Soviet era. In other words, electricity was tracked by meter and paid for according to how much of it was used in a given apartment/home, both then and now. But as the transition away from socialist infrastructure has been effected, water is another commodity that became metered and it is now common to see water meters inside apartments. As in the case of electricity, residents are now charged on the basis of how much water they’ve used each month.

On, then, to the “sanitary/sanitation day.” This sounds to me like something from 1960’s public education in the U.S. Hearing this phrase, I imagine something like a day each school year or perhaps each semester where children meet together with some sanitation representative like the resident nurse during the school day, with that person instructing them how to properly wash their hands, clean behind their ears, advising them as to how often they should bathe, and things of that sort. But in Russia, the phrase санитарный день/sanitary day is well understood and means something quite a bit different.

I was unfamiliar with the phrase until this year, when we were informed that the library in which we have hosted a couple of sessions of our English-speaking club would be closed on our preferred meeting day this week because that happens to be their “sanitary day” this month. Turns out that evidently all libraries here (and perhaps all museums, as I was later informed) close one day per month for cleaning. That, then, is what санитарный день/sanitary day means here in Russia, and it is accepted as a standard part of everyday life.

Looking into the matter a bit more deeply via an internet search, it turns out санитарный день/sanitary day actually officially became a part of Russian life and culture fairly recently. It seems an order from the Ministry of Culture of the Soviet Union dating to the year 1975 is responsible for the official enshrinement of this custom, and from about that time on, it became a standard part of Russian life and culture. So that is another aspect of Soviet life that persists in modern-day Russia.

I don’t recall from my life in the U.S. any sort of analogous phenomenon. In the U.S., libraries typically have a janitorial staff that comes in to do clean-up, mostly after hours. Though some cleaning, such as emptying garbage cans, may occur during working hours, most of the more major cleaning tasks happen outside operating hours in U.S. libraries—I think typically on a daily basis. Perhaps a few times per year a more major cleaning is scheduled but, so far as I understand it, that is all done outside the library’s regular hours of operation. I infer from the way the situation differs here that, in Russia, there is no janitorial staff that looks after the library, but that the library employees must themselves attend to cleaning duties for their location.

Look, in a future posting, for an entry regarding Soviet-era radio. I found in the apartment where we’re staying an old radio (by the looks of it I’d say it dates from the 1960’s or 70’s) from that period and I plan to post an accompanying photo and explanation.